Origins of Japanese Aesthetic Philosophy

Japanese aesthetic philosophy emerged from a rich blend of cultural and religious traditions. The unique Japanese view of beauty centers on the acceptance of impermanence and finding grace in simplicity.

Influence of Zen Buddhism

Zen Buddhism shaped Japanese aesthetics through its focus on simplicity and mindfulness. The practice of meditation influenced how Japanese artists and philosophers viewed beauty in everyday moments.

Buddhist teachings about impermanence led to the appreciation of fleeting beauty. This concept shows up in arts like tea ceremony and flower arrangement.

Zen monks developed many of the aesthetic principles we see in Japanese gardens. They created spaces that encourage quiet reflection and appreciation of natural forms.

Traditional Shinto Perspectives

Shinto beliefs added a deep reverence for nature to Japanese aesthetics. The idea that spirits exist in natural elements led to careful observation of seasonal changes.

Traditional Shinto shrines demonstrate pure, unadorned design. Their architecture emphasizes clean lines and natural materials.

This native religion taught respect for the inherent beauty of raw materials. Wood, stone, and paper remain untreated to show their natural qualities.

Early Literary and Artistic Influences

Court poetry from the Heian period (794-1185) established many aesthetic ideals. Poets wrote about beauty in subtle moments, like moonlight on snow or autumn leaves falling.

The Tale of Genji introduced complex ideas about beauty and refinement. Its descriptions of court life shaped Japanese artistic sensibilities.

Early Japanese painters developed techniques to capture fleeting moments. Their work often focused on changing seasons and natural phenomena.

Noble families preserved and passed down aesthetic traditions through arts like calligraphy and painting.

Key Concepts of Beauty in Japanese Philosophy

Japanese aesthetics embrace unique perspectives on beauty that focus on imperfection, transience, and the subtle nuances found in everyday life. These philosophies shape art, design, and daily living.

Wabi-Sabi: Imperfection and Impermanence

Wabi-sabi finds beauty in the incomplete and modest. I see this concept reflected in cracked pottery, weathered wood, and asymmetrical designs.

This philosophy values simplicity and authenticity. A handmade ceramic cup with uneven edges carries more beauty than a perfect machine-made vessel.

Time and wear add character to objects. The rustic patina on old copper, faded fabrics, and worn wooden floors exemplify wabi-sabi’s celebration of natural aging.

Mono no Aware: The Pathos of Things

This concept captures the gentle sadness and deep appreciation of life’s fleeting nature. Cherry blossoms serve as a perfect symbol – their brief bloom reminds us to cherish temporary moments.

I notice mono no aware in seasonal changes and everyday transitions. The last warm day of autumn or the final page of a beloved book carries special significance.

This awareness creates a bittersweet appreciation. Rather than fighting against change, mono no aware teaches us to find beauty in life’s temporary nature.

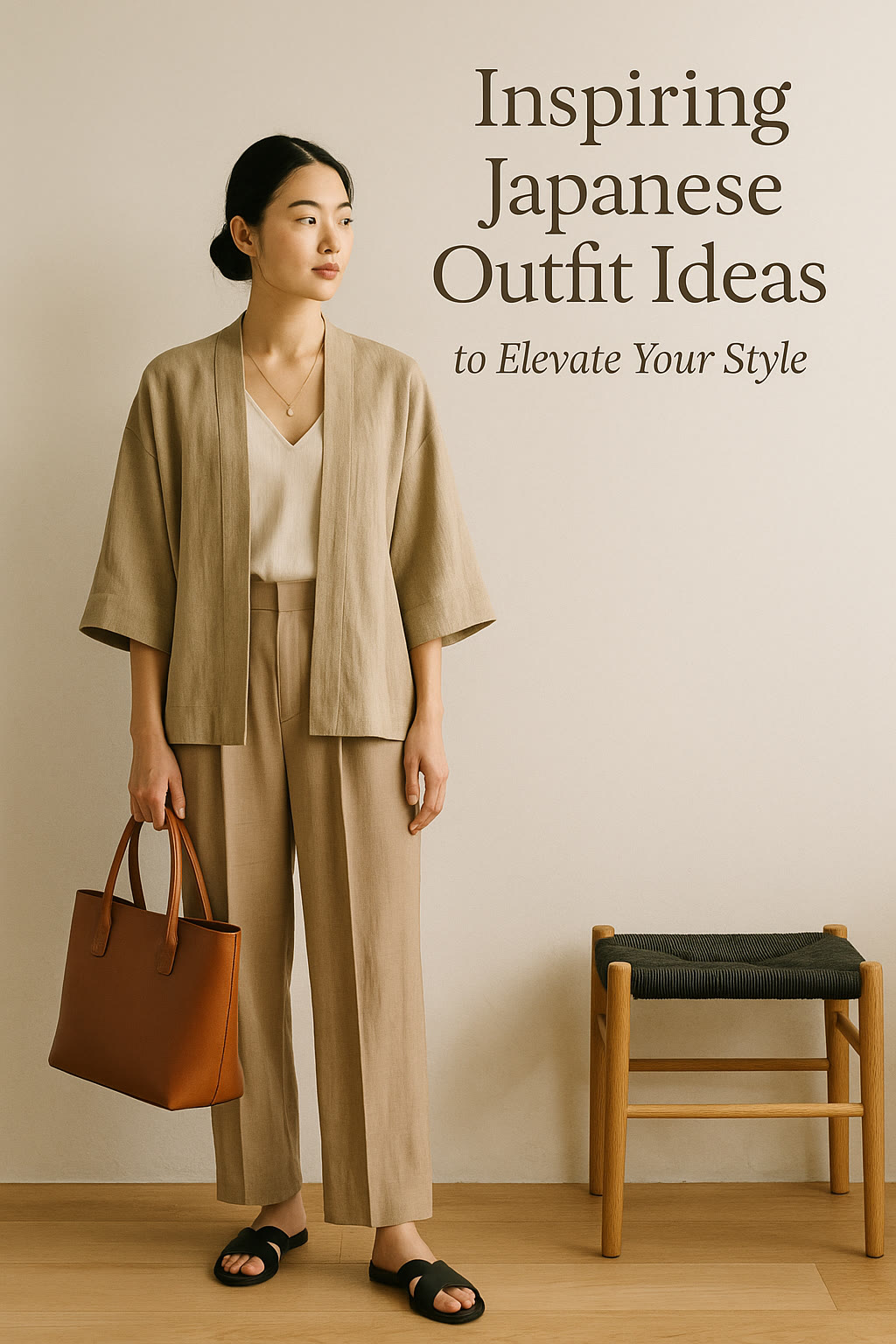

Iki: Chic, Style, and Spontaneity

Iki represents sophisticated simplicity and effortless refinement. I find it in subtle elegance rather than flashy displays.

This aesthetic prizes originality and naturalness. A simple brush stroke or minimalist design can embody iki when executed with skill and restraint.

The concept emphasizes sophisticated restraint. An iki expression avoids both the overly formal and the too casual.

Yūgen: Depth and Subtlety

Yūgen captures the profound, mysterious aspects of beauty. I see it in the mist shrouding mountain peaks or moonlight filtering through clouds.

This concept values suggestion over explicit statement. A partially hidden view or subtle hint often carries more beauty than full exposure.

Artists use yūgen to create depth through minimal elements. A few brush strokes suggest an entire landscape, leaving room for imagination.

Modern Interpretations and Application

The ancient Japanese concept of finding beauty in imperfection has evolved into practical applications in today’s art, design, and literature. I see these principles influencing creative expression and daily living across cultures.

Contemporary Art and Architecture

Many modern artists embrace asymmetry and rough textures in their work. I notice galleries featuring ceramics with visible cracks filled with gold, following the kintsugi tradition.

Buildings designed by Tadao Ando blend raw concrete with natural light, creating spaces that celebrate simplicity and imperfection.

Artists like Isamu Noguchi created sculptures that mix natural stone shapes with refined elements, showing how traditional aesthetics adapt to modern forms.

Japanese Design Principles in Everyday Life

Simple, natural materials dominate modern Japanese-inspired home design. I find this in unfinished wood furniture and handmade ceramic dishes.

Popular Design Elements:

- Mismatched dining sets

- Natural fiber textiles

- Weathered metal accents

- Raw stone surfaces

Minimalist spaces with a few carefully chosen items reflect the value of simplicity.

Philosophy in Contemporary Japanese Literature

Writers like Haruki Murakami weave traditional concepts into modern stories. His books often feature simple moments that reveal unexpected beauty.

Recent novels by Yoko Ogawa explore the beauty of ordinary life and passing time. I see how she captures fleeting moments in precise detail.

Many contemporary Japanese poets use spare language to describe everyday scenes, showing beauty in common experiences.

Prominent Philosophers and Thinkers

Japanese philosophy has produced remarkable thinkers who shaped ideas about beauty, spirituality, and craft. Their insights continue to influence modern understanding of aesthetics and mindfulness.

Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki: Promulgator of Zen

D.T. Suzuki introduced Zen Buddhism to the West through his extensive writings and lectures at Columbia University. His work bridged Eastern and Western thought during the early 20th century.

I find his interpretation of Zen particularly important in how it shaped Western views of Japanese aesthetics. He explained complex concepts like wabi-sabi and mindfulness in accessible terms.

His books, including “Zen and Japanese Culture” (1959), explored how Zen principles influence Japanese arts, from tea ceremony to painting. He showed how meditation and daily life become one unified experience.

Yanagi Sōetsu: The Beauty of Handicrafts

Yanagi founded the Mingei (Folk Crafts) movement in the 1920s. He celebrated the beauty in everyday objects made by anonymous craftspeople.

His concept of mingei highlighted the special beauty found in handmade items used in daily life. He valued simple pottery, textiles, and woodwork created without pretension.

Through his writings and the Japan Folk Crafts Museum, he preserved traditional crafting techniques. His ideas still inspire modern makers and designers who value authenticity in creation.

Nishida Kitaro: The Philosopher of ‘Place’

Nishida created the first original philosophy system in modern Japan. As founder of the Kyoto School, he combined Eastern and Western philosophical traditions.

His concept of basho (place) offered a new way to think about existence and experience. He saw reality as an interconnected field where subject and object become one.

His work changed how we think about art and beauty. Instead of seeing beauty as separate from the viewer, he taught that we participate in beauty through direct experience.

Frequently Asked Questions

Japanese aesthetics blend philosophical principles with daily practices and artistic expression, creating a unique approach to finding beauty in the ordinary and imperfect.

What is the concept of Wabi-sabi in Japanese aesthetics?

Wabi-sabi embraces the beauty of imperfection and natural aging. It teaches us to find meaning in simple, rustic, and worn objects.

I see wabi-sabi in cracked pottery, weathered wood, and autumn leaves. These items tell stories through their imperfections.

How does Wabi-sabi philosophy reflect on everyday life in Japan?

Japanese people apply wabi-sabi by keeping modest homes and appreciating natural materials. They value handmade items and respect signs of age.

I notice this philosophy in Japanese gardens, where asymmetry and natural growth patterns take priority over strict organization.

Can you explain the historical origins of the beauty ideals in Japanese philosophy?

Beauty ideals in Japan emerged from Buddhist teachings about impermanence and simplicity. These concepts took root during the tea ceremony traditions of the 15th century.

Zen Buddhist monks played a key role in spreading these ideas through their arts and practices.

In what ways is Japanese philosophy of beauty evident in their art and culture?

I see Japanese beauty philosophy in ikebana flower arrangements, where space and simplicity matter as much as the flowers themselves.

Traditional pottery celebrates uneven glazes and natural textures. Poetry often focuses on fleeting moments in nature.

How do Japanese beauty concepts influence modern interior design?

Modern homes use natural materials like wood and stone. Spaces remain uncluttered with minimal decoration.

Light and shadow play important roles, creating depth and atmosphere in rooms.

What are some famous quotes that encapsulate the Japanese philosophy of beauty?

“In darkness, beauty glows” – Japanese proverb

“Less is more” reflects the Japanese mindset toward beauty and design.

“The perfect is truly found in the imperfect” captures the essence of wabi-sabi.